World Elephant Day

Dandelion. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

Every color I see is really a color rejected. Elephants are gray because gray is the color of the wavelengths of light reflected from the surface of their skins. Blue jays are blue and daffodils are yellow for the same reason. It’s possible for our eyes to gorge on a thousand or more different color combinations – tints of turquoise, hues of hyacinth, shades of sapphire. For proof, simply go to the nearest paint store.

But the colors I see are not the colors seen by elephants or by snakes or by insects or by cats and dogs. Many scientists after many experiments believe that cats and dogs do not see colors well, but that birds do, and that the colors of their feathers have a lot to do with either camouflage or sexy come-ons. They must be right. Otherwise we would endure male dogs with tails like peacocks and female cats with hind ends as red and swollen as baboons.

The colors I see, and the subtle natural variations of them, were of considerable advantage to my ancestors, foraging primates swinging down from the trees into the lion-colored grass. Colors indicated ripe fruit and patterns — the difference between zebras and leopards.

To honeybees, the world as I see it moves like molasses. Each eye of the honeybee contains nearly 7000 lenses — 7000 pinpoint openings for light, giving it composite images shaped somewhat like snow globes. Homing in on flowers at 300 images per second, (vs. 60 per second for humans) bees zoom about in fast-forward, so they can make all those in-flight adjustments to the slightest change of wind, grasp all those swollen bodies of pollen.

Like us, honeybees have three photoreceptors in their eyes. Where we see blue, green, and red, bees perceive blue, green and ultraviolet, combined into colors entirely different from those we see. Ultraviolet patterns on flowers are invisible to us, but to bees those patterns announce seductive landing zones.

It’s been long speculated that creatures with compound eyes see far less efficiently than we do. But seeing is in the eye of the beholder, in the language of colors available to read. Where I might not even notice a certain flower a besotted bee ogles an orgy of ultraviolet ravishment, an irresistible, come-hither promise of pollen and nectar.

I want the language of bees in my head, to see the world differently when I write. I want my words to unfold like time-lapsed flowers, petal pushing against petal, blooming in foreign color combinations, perennial, glorious, sexy, irresistible. I want you to stick your nose inside my flowers, waggling and buzzing. I want you to come away pollinated.

Swollen by November rains, the Okavango River floods south from Angola, arrives in Botswana in May or June, fans out, and then stops when it bumps into a barrier of fault lines near Maun. Landlocked, the river penetrates deep into the Kalahari Desert before it dies in the sand. Not a single drop reaches the sea.

As the river pushes south, it creates an oasis, a floodplain the size of Massachusetts, containing an ark-full of animals: the Okavango Delta, a flat maze of islands and water.

The river descends less than 200 feet in 300 miles. Bracketed by fault lines, sediments deposit elevation changes of less than seven feet. Islands that rise above the floodplains tend to be long and sinuous, following old channel routes, linking to other uplifted channels, and creating large dry fingers of land that will be outlined by next season’s floods. Water loving trees such as the Jackalberry, Mangosteen, Knobthorn and Sycamore Fig fringe these larger islands.

The Delta contains more than 50,000 islands; their landmass roughly equals that of water. Paths cross some of the islands; roads cross others; water surrounds the rest. All of the islands carry the mixed vegetation of the Kalahari sand plains. Approached by foot in this maze, every island looks like the next one and the next one and the next, especially during the low flood season, when boundaries between them evaporate with the water, when footpaths end in walls of thick bush, and roads take every opportunity to wander off in a new direction.

Near the southern end of the Delta, some of the islands are larger sand-veldt tongues, extensive areas of the Kalahari that penetrate deep into the flood. In the Okavango’s vast delta of islands, a few inches here or a few inches there separate wet lagoons from dry land.

If I turn one way, I’m lost in a maze of floodplain islands, now high and dry. Turn the other, and I’ve entered into a maze of Kalahari woodland. Until I’ve gone a few miles, it’s hard to tell the difference since the same vegetation covers both.

When the sun sets, magic begins. The sky turns orange; water lilies fold into perfect imitations of floating candles; papyrus along shorelines become golden sentries; and the spell of water over a desert casts its memories into my dreams.

In 1775, my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather came to America from France to help the colonists fight for independence from the British. He was 24 years old. Born in Marseilles to Lady Anne de la Lascour and Admiral Antoine Garoutte, Michel Antoine Garoutte was also born into the nobility of Provence in France, ruled at that time by Louis IV. He was educated to be a Catholic priest until the age of 15 when his older brother died in battle. Michel left the seminary and went to Military School and Officers School, the same schools as his friend, Lafayette.

Both Michel and Lafayette became convinced that the American settlers’ fight for liberty was a just cause. That it was better to have rules of law fashioned for the majority of citizens rather than laws made by edict, made by just one man. Michel was not looking for a new start on life; he was not looking to farm his own land; he was not fleeing persecution – he was fighting for a new concept of governance: democracy over monarchy.

Michel outfitted two ships at his own expense and sailed to the New York Colony. Even though he was from wealth and nobility, he became a pirate and a privateer, overtaking British vessels, seizing ammunition, artillery, and other goods to supply General George Washington’s army at Valley Forge through Little Egg Harbor, which privateers used as a home base.

At the Battle of Chestnut Neck near Little Egg Harbor in 1778, the British burned Michel’s boats and destroyed other supplies before they withdrew under threat of superior patriot forces arriving.

His named now Anglicized to Michael Garoutte, he served on the brig-of-war Enterprise and sloop-of-war Racehorse.

Shortly after the Battle of Chestnut Neck, he went ashore to help a friend hiding in an Inn that aided revolutionaries. Ambushed and bayoneted, he was left for dead. The innkeeper John Smith, a Quaker, found him and brought Michael to his inn, where he was tended to by the innkeeper’s daughter, Sophia. They married in 1778. He was 28. She was 19. They had 14 children together.

After the Revolutionary War Michael and Sophia started a tavern: the La Fayette Tavern in Pleasant Mills, New Jersey. La Fayette visited the tavern and stayed at its inn on his various trips to the newly-formed United States. Michael died at the age of 79 and is buried in the Pleasant Mills Cemetery in New Jersey. The tavern no longer stands. The gravestones at the cemetery are so eroded that his name can no longer be found.

An immigrant who owned castles and could have lived a life of extreme luxury became a commoner in the country whose founding laws he believed in. He fought for the rights of citizens in his adopted country. He didn’t go from rags to riches; he went from riches to just getting by because he did not believe that one man should rule all others; that citizens had the right to govern themselves. His life was like that of many immigrants — fighting for the country they believe in. And still believe it’s worth fighting for.

https://julian-hoffman.com/2025/06/06/lifelines-a-books-beginnings/

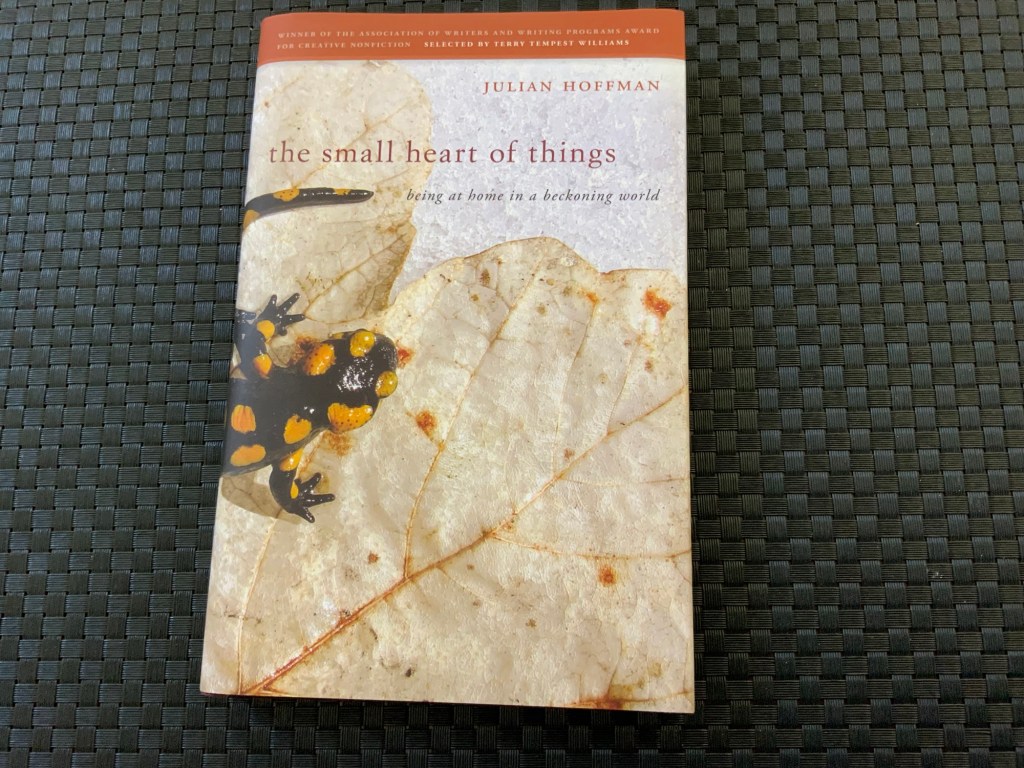

Julian Hoffman’s The Small Heart of Things is a wonderful book about the connections between the many “small things” in our lives that, taken together, create who we are and how we see this amazing world we inhabit. I can’t wait to read his new book, Lifelines. He lives and writes from a place of beauty, history, and wildness: the Prespa Lakes – hemmed by the countries Greece, Albania, and Macedonia. I expect to be amazed once again.

When I least expect it, Beauty fells me with a roundhouse right, pummels me with soft fists, dazzles me with her quick feet. Sometimes it’s a glancing blow to the chin; sometimes she doubles me up by a quick swing to the solar plexus. Right, left, right, left – she dances me round and round the ring until I lose my breath and leaves me dangling in my corner, dazed and gasping. She often holds me in a clinch, face to face, with nothing more to say.

To some Beauty is just another word, but in bouts with me she’s always the champ, always the champ.

I’ve finally finished my memoir, Larger than Life, Living in the Shadows of Elephants, and I’m sending queries to agents. In the meantime I’ve begun a new project, a fictional account of my ancestors’ experiences on the Oregon Trail, Her Diary, Unwritten. I want to redesign this website to be able to reflect both books, and will be working on that soon. Thanks everyone for following me in the past. See you again soon!

Nonfiction is not made up, right? But I wanted to wander off into my imagination while writing this essay and this is the result, just published in Sentience Literary Journal:

We are born. We die. In-between, ah, in-between are all the possibilities in the universe.

What brings it all forth? What have we in common with every living thing? What have we in common with the vine tendril, the bee, the unfolding flower, the cheetah, the salmon, the amoeba?

O each vanishing endangered one upon this earth, the last ones, the least ones, the ones we rarely see, the ones we will never see again. O the sun, the wind, the rain, the mountains, the deserts, the trees, the seas, and all who live around us, despite us – what a spell of life you cast!