In 1898, on the central coast of British Columbia, Franz Boas recorded oral beliefs of the Heiltsuk tribe. Their creation stories told of a world made of water and ice and a narrow strip of shoreline. The oral history of the Heiltsuk stated that their peoples settled the central coastal area “before the great flood,” which may refer to the rising sea levels as ice sheets further inland melted.

The First People of North America spread up rivers and along the Rocky Mountain foothills, out into the Great Plains and on to the Atlantic seaboard as the glaciers melted. Twelve thousand years ago, a band of humans travelling the steppes of what would become the state of South Dakota, might have witnessed something like this:

To the north are huge, receding remnants of the Pleistocene glaciation. But here it is spring, and the valley below them bursts with sedge, Arctic sagebrush, dwarf willows, buttercups, daisies and new shoots of grass. A braided river born from ice meanders south, glistening under a rising sun.

In the distance immense clouds pile behind a series of small, rolling hills. The clouds groan, rumble and rain fingers the earth. A rainbow arcs, glistens, and fades.

Up and over the nearest hill strides a Columbian mammoth, and then another and another, until the horizon holds thousands of them in parallel lines, headed in a single, purposeful direction. It’s the spring migration, following a route used for generations.

The humans squat, clothed in the skins of llama and deer, rabbit and fox. They watch as the mammoths fill the basin below them. They watch interrelated family units greet each other joyously, trumpeting, bellowing and intertwining trunks. The air shivers as mothers rumble reassurance to their offspring. The circles of kinship within the mammoth families include aunts and grandmothers, uncles and grandfathers, whose experiences carry the entire library of mammoth knowledge.

A young calf with wild eyes and a swinging trunk veers out of the herd and toward the humans, stops, lifts a foot, raises her chin, then rips out a clump of grass and throws it over her back. As a self-appointed guardian for her family, she’s young enough to be uncertain and old enough to be full of herself.

Satisfied with her display, festooned with wisps of grass, she rejoins her family. A sibling tugs at her fur, liberates a stalk of grass and waves it around like a magic wand. Her mother, the matriarch, is constantly alert to the humans, her awareness evident by an uplifted trunk smelling in their direction.

The humans keep an eye on her. They know what she’s capable of if they threaten the herds. They watch and wait, scanning the valley, smelling sweet grass crushed between thousands of massive molars.

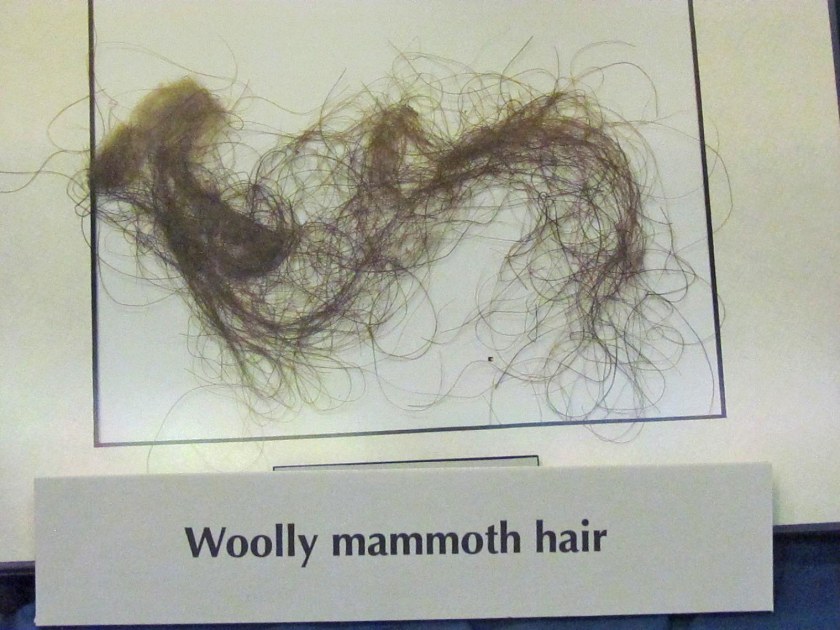

On a distant hill a solitary male mammoth flips over shocks of grass, searching for new growth. He’s an oddly dainty monster, with a squashed, flattened face and a tall head dome. The skirt of hair across his flanks and under his belly ripples in the breeze. His fur coat is three feet long, his feet covered with six inches of hair. Around his neck and under his chin, is a dark-colored beard, a feature often depicted by Ice Age artists.

The humans communicate with silent glances at each other, recognizing the woolly mammoth is old and slowed by age. They are not surprised when he is surrounded by a pride of American lions, Panthera leo atrox, a species 25% larger than today’s African lions. Timing and opportunity are gifts to all predators.

The lions surround the mammoth as he stands his ground, whirling in circles, brandishing his tusks. The more agile lions slice in and out of the fray and finally succeed in hamstringing the bull, severing the tendons of both back legs. A long time later, the mammoth goes down. The lions eat their fill and spend most of the afternoon upside-down, napping. The humans settle for a long wait. Often lions will defend prey this size for days on end.

But humans aren’t the only hunters following the herds, waiting for opportunity. Other scavengers are drawn to the kill. Circling in a slow funnel of doom, paratroops of vultures spiral down, down, down and muster on the ground in untidy rows. A group of Condors, slump-shouldered and patient undertakers, perch on a jumble of nearby rocks.

At the first hint of blood on the breeze, Arctodus simus, the Giant Short-faced Bear, stands upright on his two back legs, sniffing for the direction of its source. The biggest bear ever – twice the size of a grizzly – he is 11 feet tall when upright. Like all bears, he is also an opportunistic carnivore. With olfactory organs larger than those of any other bear, he locates the lion kill quickly and strides toward it at a graceful, rapid pace, moving in the same way a horse paces, the legs on a side moving forward together. He does not waddle like modern bears. He charges up the hill, roaring. The lions give way to the largest land predator of the Pleistocene, intimidated by his size. They are unwilling to risk injury from his strong jaws and their ability to crush bones with a single bite.

The humans stay put and let the bear eat. They too are intimidated. Even when standing on all four legs, Arctodus simus is seven feet tall, able to look any man directly in the eye.

Toward dusk, when the bear shows no signs of moving on, the humans concoct a plan. They gather stones, large stones, and ferry them within throwing range. The bear stands erect each time the humans edge closer, but is glutted, lethargic, and does not charge them. The humans spread into a half-circle, each one next to a pile of stones, and with a single nod, begin to throw as fast as they can. Surprised, furious, the bear charges in one direction, only to be hit from another. Before their piles of stones diminish, the humans have routed him. They are many and he is just one.

They build a ring of low, smoky sagebrush fires around the mammoth. They cut out his tongue and eat it raw. Fortified, they work through the night, scattering coyotes with well-timed stones. They carry a small arsenal of bone-tipped spears and arrows, but these are precious and not used unless it is absolutely necessary. Wolves, howl at a distance, pack-hunting under a full moon.

More than half the mammoth, the down side, is still left. One of the men separates an exposed shoulder blade from the rest of the skeleton and sharpens it by flaking away pieces of bone. At thirteen pounds, it’s a heavy tool. He uses both of his hands to chop at the carcass. He hacks at a lower leg, frees it, and and drags it to one side.

A woman uses a splintered tibia as a knife, shaves layers of fat from a disarticulated foot. She eats as she shaves, wipes blood and fat from her face with the palm of her hand, and pushes her hair from her eyes. It clumps in crests like greasy, matted feathers. She swats at the mosquitoes swarming around her, then rises and throws dried mammoth dung on the nearest fire. It smokes, repelling the small, persistent predators, a species so adaptable it will live on long after both mammoths and humans vanish from the earth.

Under the cold, unblinking animal eyes of the night sky, in a world lit only by a small circle of fires, the humans eat and butcher and sometimes sleep.