Driver’s Education

The last thing I expected for Game Ranger Training was driver’s training, but right now I’m learning how to parallel park next to a bull elephant.

“A little right,” says Syd, and we flatten yet another bush with a loud crunch. Our noise doesn’t seem to bother the elephant. He’s placidly stripping the bark from a small acacia while I wrestle the wheel.

“Okay,” Syd says, “shut off the motor, but leave it in first gear.” As soon as I do, cameras click and whir as five other trainees happily snap pictures. My fingers tremble on the keys and my left foot goes numb on the clutch while I watch the elephant’s mood. He’s no more than ten feet away, browsing out of a patch of sunlight and into shady thornbush. The cameras cease clicking.

“Move over there,” Syd points to the other side of the elephant. “Light’s better.

Good positioning for photo ops is probably an important skill to acquire to guide tourists through the wilds of Africa. But getting to where Syd points will not be easy. There’s a log to crawl over and a hole to avoid that’s big enough to swallow a rhino. But the real trick to driving a 12-passenger Land Rover is not to bounce anyone out of the last tier of seats. It’s a good five feet off the ground. Already I’ve navigated a 30-degree slope out of a sandy riverbed without losing anyone over the side, even though the backend of the vehicle fishtailed as if on ice and all I saw was the sky until all four wheels were on level ground again. I figure if I get close to the elephant again, I’ll pass this informal driver’s test for sure.

Down, up, squeezed between two large tree trunks, the Rover crunches dry branches under its tires, making more noise than the bull, who’s busy dismantling a large rainbush. Without any directions from Syd I park at an angle that gives everyone a clear shot. I turn off the motor. Engine vibrations cause blurry photographs.

“Oooo, good light,” someone says and the cameras resume their consumption of film.

Syd smiles at me. I’ve passed. He hands over my camera. “A very calm elephant. You can take pictures, too.”

As I focus the bull begins to look a lot like the elephant who hangs around our camp, the one with the chipped left tusk. Like all good teachers, Syd’s built in a little insurance to make the hard stuff easier. We’re here on a crash course with only three days to earn our training certificates. Safari guides study for months and years, both in and out of the field, so we won’t qualify for a change of careers. We only want to learn skills that might come in handy for the next leg of our trip – overland camping thorough Botswana.

Syd’s initial surprise at our wrinkled faces and gray hair was evident when he met us at the Skukuza airport. The surprise quickly turned to puzzlement as we dropped our duffels in the dust.

“Where is your luggage?”

“This is it,” I replied. “We’ve all been to Africa before.” I point to two women in our group. “They’ve been here thirteen times.”

“Is it?” Syd whistled through his teeth, the South African equivalent of really?

The camp Syd works for is located in a private conservation area on the southwest edge of Kruger National Park. It’s between the fork of two rivers, the Sabi Sabi (meaning “Danger! Danger!”) and the Sand River, now a dry and treacherous streambed filled with boulders – the site of my diver’s test.

The bush we drive through was once the home of the Shangaan, whose land was sold to a private concession. Syd takes us to the place where his father had a rondavel and kept cattle. Flattened areas mark the spots an entire village once occupied.

“My father received no payment from the former government,” Syd tells us. However, the new South Africa is talking reparations and Syd is proud of this. “Our government is trying. It is all we can ask.”

Although two luxury bush lodges are close by, we’re definitely roughing it. We pump our own water, take bucket showers and eat meals around a campfire. We live in tents set up on platforms above a concrete pad. In the warm season the elevation keeps snakes and smaller creatures from crawling into sleeping bags, but now, at the height of winter, nothing but cold air creeps under our cots.

Last night I wore my gloves, stocking hat, long underwear, sweatshirt, socks, sweater – nearly everything in my duffel and still woke up shivering.

This morning I burst out of my sleeping bag’s cocoon, jam my feet into boots, then simultaneously dance into my pants and pull on my coat. I scamper to the fire and shove my boot tips into the coals.

A blackened coffeepot simmers inches away.

“It snows where I live,” I say to Syd, “and it’s not this cold.”

“I don’t believe you,” he laughs.

“I’ll show you.” I jog back to my tent and fetch a small album I brought, photos of my house, of family and friends.

Syd stares at the picture of my car, a white lump, identifiable only by its black side mirrors sticking out like ears. He stares at the picture of our road – blanketed fir trees bracket a single set of tire tracks. He points to a fir.

“Christmas,” he says, “your Christmas.” He has never seen these dark conical trees with needles. “They are still green.”

I tell him that I was warmer then than I am now.

“No, no,” he laughs and points to the picture of our house; his finger traces the furrow my legs made through the snow. “No, this is colder.”

I stamp my feet to waken my toes.

A few minutes later Syd takes us out on foot to read spoor and learn the botanical lay of this land. In the soft early morning light the trill of a coucal follows us, sounding like water dripped into an empty metal bucket. Doo-doo-doo-doo. . . doo . . .doo. . . do.

The coucal’s rust-and-black feathers provide perfect camouflage in the dry winter bush. We peer into the scrub, but do not see him.

Most of the rattles and flutters we hear as we walk are birds, but each one makes us scan the bush nervously. We’re on foot with lions, leopards, snakes, and elephants all around, and absolutely dependent on the knowledge of just one man.

Syd shows us how to sort out the difference between the tootsie-roll droppings of wildebeest and giraffe – a wildebeest stands in one spot, thus a pile, while a giraffe walks, spreading droppings along its path. In contrast, hyenas eat enough bone that their scat looks like chalk. Syd picks up a piece and it crumbles in his hand. We step over the dung of an elephant, easily identified by quantity – a five-gallon bucket of compost dumped into a pile.

Just in case we might need it, Syd also shows us weeping wattle, which can be used for toilet paper or bed stuffing – its leaf clusters soft as any paper product on the market.

As we walk we sample the sweet, fibrous inner lining of acacia bark, a favorite of elephants. We taste a creeping vine called elephant pudding; its succulent leaves have the flavor of salty green beans. Syd gives us a single leaf from a Magic Guarri to chew, but I quickly find out there’s nothing magic about it. Guarri has so much tannin that it tastes like a never-cleaned copper teapot. Even elephants won’t eat it, and elephants eat almost anything. Syd doesn’t tell us that until after we spit out the bitter leaves.

Our hike takes us past a Marula tree, which bleeds a sap red as blood. Dye is made from its bark and sweet liquor from the fruit. The fruit has four times the Vitamin C of an orange. Just next to the Marula is a potato bush, which exudes the scent of fried potatoes, but only at dusk as its sap rises.

Later on, in the evening, Syd proves himself as good a cook as he is a teacher. Tomatoes fry in one cast iron pan, while a chicken stew simmers in the other. He deftly drops dumplings into the stew, covers it, and pulls it to one side of the fire. He passes out tin bowls and spoons. We scoop and set speed records for consumption, wash our bowls with sand and rinse in a tiny amount of water.

Night falls fast in Africa. In the gloom deepening into blackness we climb aboard the Rover and wrap ourselves in felt-lined blankets. The temperature is quickly dropping, just like in high deserts: shirtsleeves at noon, long underwear right after sundown.

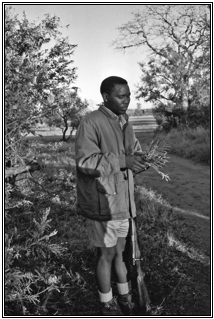

Syd drives us to one of the nearby luxury lodges where we pick up Bernardo, a tracker. He is young, with a wide, brilliant grin and an obvious deference to Syd. We have the feeling he is in training also, and Syd confirms this. “I was once a tracker like Bernardo.”

Bernardo wants to know the results of our driving test.

“Who is the best?” He asks Syd.

Syd points to me.

“Is it?” Bernardo glances doubtfully at the only male in our group. I smirk and reply, “He drives too fast.”

How either of them will find anything in the gray twilight is a mystery to me, but Bernardo settles onto a canvas seat perched on the front of the left fender. Although it’s a little like riding a mechanical bull, from there he’s able to see any tracks in the sandy ruts before we drive over them. In ten minutes we are on the trail of a rhino.

Syd and Bernardo are excited. They leave us in the vehicle and walk ahead, trying to read the rhino’s intention. Bernardo waggles a finger at us when they return.

“You are very lucky,” he says, his smile a sunbeam through the gloom, “not many rhinos here.”

Ten minutes more and we find him, right beside the road. It’s doubly lucky that he’s a male; females with calves will charge anything that moves. The rhino ignores us. He’s found some fresh green grass, an unusual treat in the dry winter season, and he’s busy cutting a large swath through it, snorting as he eats.

Fhufff. Chomp. Chomp. Chomp. Fhuffff. Chomp. Chomp. He sounds like the world’s largest steam-driven lawnmower.

We sit in silence, watching a prehistoric creature. I half-expect a dinosaur to emerge from the surrounding bush and join in the grazing. Mist rises from the wet grass and obscures the black outline of trees against a sky that is now dark violet. The rhino moves off, disappearing into a smudge of brush. But we can still hear his progress: Fhufff. Chomp. Chomp. Chomp.

On our way back to camp I catch a glimpse of movement in the tall grass. “Leopard!” I whisper and tap Syd on the shoulder. Bernardo turns in his fender chair and quickly spots him too, motioning with an arm. Syd drives in a wide circle, cutting across a clump of brush. Even though we’re making more noise than the rhino did, the leopard is intent on something far more interesting: the nearby snorts of jittery impala.

He crosses the road behind us, then changes his mind and walks down the middle of it, in our wake. We stop and Syd shuts off the engine. The leopard lopes by on the right, too fast for my camera’s shutter speed. He passes under Bernardo’s feet.

Bernardo is frozen. He doesn’t even look down. By remaining motionless, he becomes part of the vehicle and the leopard ignores him.

When the leopard is twenty feet away Bernardo exhales, relaxes. He turns to us with his sunburst grin. “Oooooh you are lucky! A rhino and a leopard!” He shakes his head from side to side. “You are very lucky!”